Education

How to grow trees in a marmalade factory?

Zala Gruden

Jun 02, 2022

What if we told you that it is possible to teach data mining to kids in elementary school in an enjoyable way? You’d say,

"Impossible!" and "That's too much to ask of a kid!".

We say, "Just watch; it can be done in a fun and informative way that will help these kids learn fundamental logical thinking patterns!"

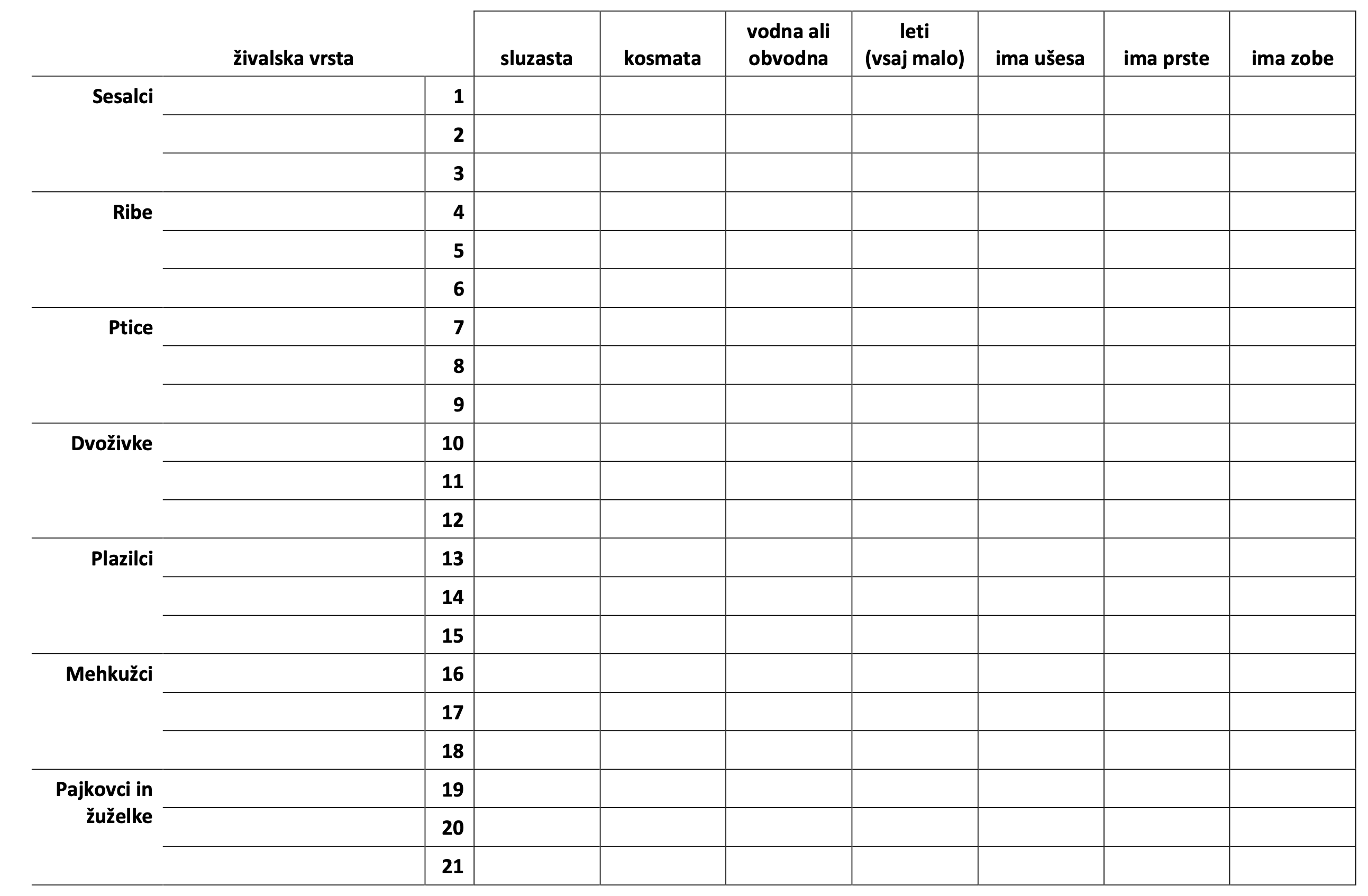

A week before our Tuesday visit, the kids from Alojzij Šuštar elementary school in Ljubljana took a trip to the Ljubljana Zoo, paying close attention to animals and their features. They were given a form (Figure 1) into which they had to enter the data for three mammals, three birds, fish, amphibians, reptiles, insects or spiders, and invertebrates (excluding insects and spiders). For every animal, they wrote the species and several features: hairy, "slimy", aquatic, has fingers, has ears, and can fly. After returning to school, the teacher entered the data into a Google Form. The children were split into 7 groups, so we had a data set with around 140 instances (some referred to the same animal, yet possibly with different data).

The form that the kids to enter their animal data into.

Remember this; we will be coming back to this story at the end!

On the day of our visit, Janez gave the fourth-graders from the Zoo a new task - character classification.

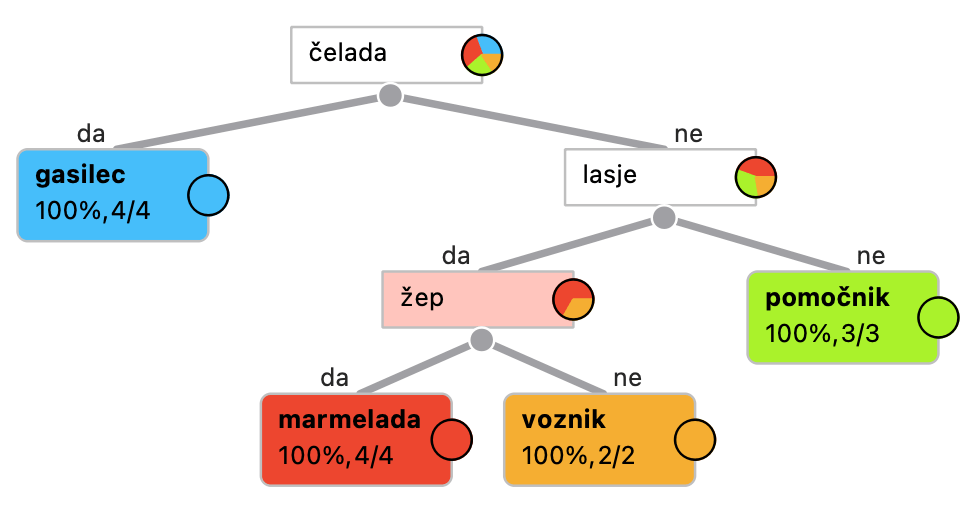

We showed them four characters: one working in a marmalade factory (M), an assistant (P), a driver (V), and a firefighter (G) (letters are derived from corresponding Slovenian words). They were all slightly different (having a helmet or not, having a pocket or not, two hairstyles, one- or two-eyed, different mouths). We also showed them two unlabelled images. Children immediately began hypothesizing how to recognize their professions.

We split the children into groups. Each group received 20 cards with charachters, 7 of which were unlabelled (Figure 2). Their task was to predict the profession for unlabelled characters.

The task took the children a few minutes. We wrote the names of unlabelled characters on a whiteboard and started the tedious task of assigning characters to professions.

While there was some dispute on what defines a profession, the children were quick to find their own sets of rules. They determined what defines a firefighter, an assistant, a marmalade chef. We wrote each rule onto the whiteboard, building the decision tree in the process. For example, we chose hair as one of the children's suggestions. Characters with tidy hair are assistants. For the others (no helmet, uncombed hair), they decided we should check whether they have a pocket. If so, we decided they were marmalade producers; otherwise, we decided they were drivers. (Children hypothesized they need pockets to steal marmalade; another idea was they need a pocket for the recipe.)

Having drawn the tree, we took the pictures of unlabelled characters and classified them by following the tree. The children agreed that this was a helpful procedure and could be used for other similar tasks.

This brings us back to the data from the children's visit to the Zoo!

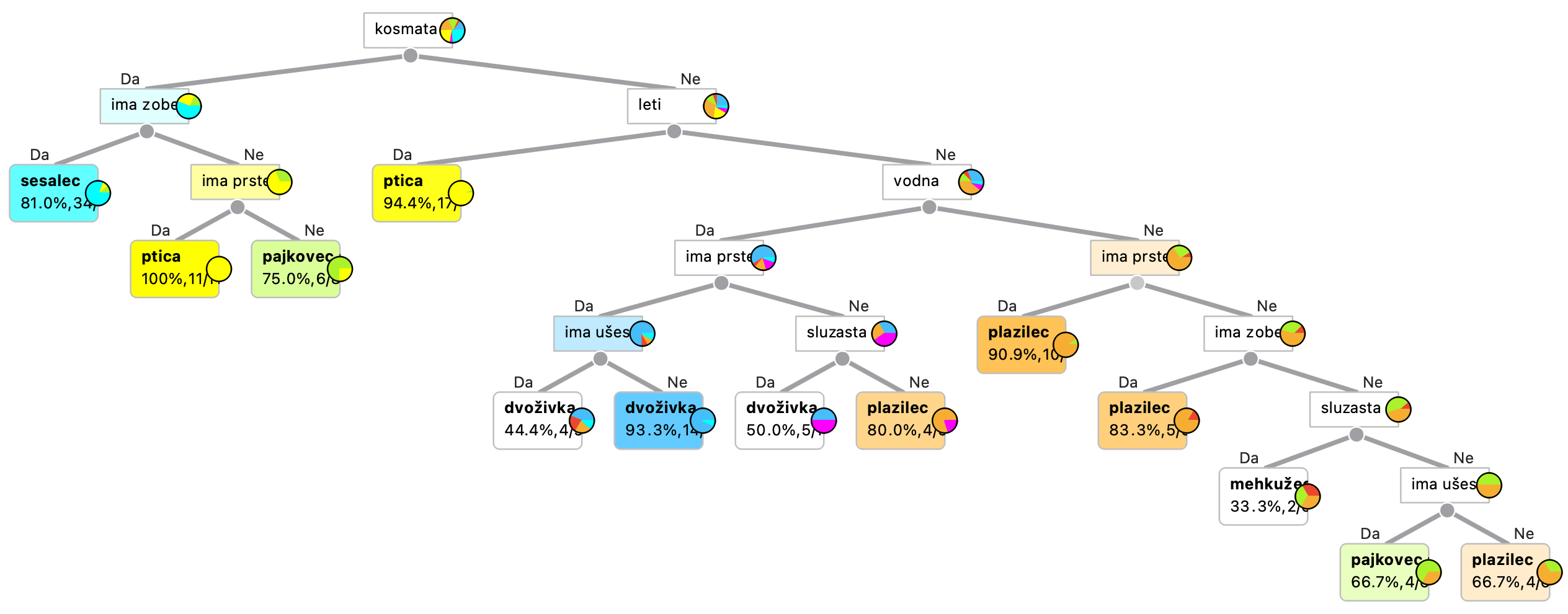

We can use the same type of activity with the data the children collected while observing animals. Janez showed them the collected data and constructed a decision tree using Orange.

We tested if the tree works correctly by picking an animal and "manually” checking whether the tree made the correct classification.

A tree that classifies animals into mammals, birds, reptiles etc based on the data collected by children.

We checked with a squirrel, a bear, a crow, a frog, and a sea lion. The tree has correctly classified all the instances. Still, there was some erroneous data, which provided us with a beautiful lesson on the importance of understanding data before analyzing it.

Some variables were misunderstood. Some children described birds as hairy – a Slovenian word that could, with some imagination, also refer to feathers. The term "ear" also proved to be ambiguous. Some children have noted that all animals must have ears, but only some have visible ears. And the visible ear was one of the determining variables.

We noticed that engaging children in creating data they created is valuable. This is particularly important for children of this age group (around 10 years old).